“As we approach 2023, you are now completing and have survived the third year of the largest, most globally coordinated psychological warfare operation in the history of mankind. During this period, on a daily basis, you have experienced the US Government and many western nations deploying highly refined, military-grade fifth generation warfare technologies against their own citizens.” —Dr. Robert Malone, December 12, 2022.

So is this “globally coordinated psychological warfare operation” simply part of a mass formation derived from society’s fixation on mechanistic thinking (itself derived from Enlightenment rationality,) as Dr. Mattias Desmet claims?

In this post I’ll analyze Desmet’s book, The Psychology of Totalitarianism, to demonstrate that this book serves to obscure any overall global planning toward a world-wide system of monitoring and managing populations and instead puts the blame on totalitarian tendencies within society itself. The cause of totalitarianism, according to Desmet, is psychological: the masses, having become increasingly isolated, lonely, and atomized due to their fixation on mechanistic solutions to problems, readily turn their attention to whatever serves to alleviate their anxiety and provide certainty to their uncertain lives. For brevity, I’ll refer to The Psychology of Totalitarianism as simply, “PT”

But totalitarianism is a political problem, not a psychological problem. Yes, “masses” under totalitarianism suffer psychological problems but the origin of totalitarianism is, first, near-complete control of communication (censorship) so that the truth can’t be heard, and secondly, surveillance of the population to ensure that everyone is acting as the authorities would have them act. It’s remarkable that in a book about the psychology of totalitarianism hardly a word is said about the great danger facing society through the rapidly-growing technology of surveillance such that with sufficient “emergencies” to trigger public compliance, virtually everywhere we go, everything we buy, everything we say, and even the condition of our own bodies can be surveilled. All of our communications can be surveilled for compliance so that none of us is spreading “misinformation”— or diseases. All of this could be done due to supposed “necessity” in exactly the same way that Covid restrictions were done out of supposed “necessity.”

Propaganda is simply government censorship of opposing viewpoints so that only one narrative dominants. Propaganda is the opposite of open debate necessary for free societies.

PT says virtually nothing about this, yet one would suppose that the psychology of censorship and surveillance would figure prominently in a book on totalitarian psychology, and in a book that makes frequent references to Hannah Arendt’s analysis of totalitarianism wherein, we’re told, one of Hitler’s first plans after seizing power was “an inconceivable wave of propaganda” (footnote in Arendt’s book, page 424.) Nor does PT have any warnings for us about the potential form a new totalitarianism might take, driven not by the inexorable and self-destructive logic of a single idea— as Arendt states— but rather by a desire to control and manipulate that wishes to sustain itself rather then burn itself out in the madness of a single idea. That new form of totalitarianism might be “soft” totalitarianism, wherein we’d all own nothing but be happy, for example, because being unhappy would be something of a crime (after all, PT says that one requirement for totalitarianism to arise is widespread social anxiety.) We might imagine a world of near-total electronic surveillance wherein access to goods and entertainment and travel might be controlled by one’s social credit score. But, importantly, it wouldn’t necessarily be the same madness of total terror that consumed Nazi Germany or Stalin’s Russia, and which Arendt’s work explicates. And it wouldn’t be a mass formation at all, since the masses would be happy in their compliance and rewarded with the conveniences modern technology allows for the faithful. The unhappy and disobedient dissenters, however, might find themselves completely cut off from even the necessities of life in a world of total surveillance and total control.

The terror that Hannah Arendt speaks of wouldn’t be necessary in soft (yet still complete) totalitarianism; merely total censorship, total surveillance, and total enforcement would do. And the end goal wouldn’t necessarily have to be a single idea driven to it’s irrational conclusion (Arendt and to a lesser extent, PT) but simply a determined “greatest good” that might shift as the winds change and that allows those who envision a transhumanist future to remain in control, guiding this greatest good. Avoiding catastrophic CO2 warming would serve nicely as a greatest good, and the idea of “stay safe” could be expanded to embrace staying safe from global catastrophe as well.

Some words about logic are in order. An aptitude for logic is the ability to discern contradictions between concepts, and between concepts and reality.

As Arendt’s writing makes clear, there’s great danger in dependence on logic itself: this can lead to terror, as she so profoundly describes and as I’ll explain later. Paradoxically, a rigid dependence on the logic of one single idea for social programming leads to irrationality.

My position is that logic should be based on intuition, and within that intuition the use of logic and reason then leads to more intuition and more “seeing.” Logic helps us see more as we peer through the world of concepts and talk to each other. But without a basic intuition of compassion, without this basic seeing which can’t be described but can only be understood in a concrete, here-and-now intuition that the living world before us offers, there’s blindness.

We deal in language and concepts, and logic is essential to check our reasoning for consistency and to measure our ideas against the real world. In the world of ice-cold logic that Arendt describes when Germany and Russia were overtaken with an all-encompassing terror, there was no reference to the real world at all. The assumption then was that once a specific idea (“a classless society”; “a purified race”) was manifest on earth, then the world would be illuminated. But, the world is already illuminated even before we begin to think about what a best possible future might be: this is what intuition tells us.

We depend on logic to help determine truth. Narratives can describe reality but they depend on the “checks and balances” of logic and reason. Narratives may be true or false, or may be somewhat misguided. If we throw out logic and depend on narratives alone, then the contradictions between narratives and reality are left unchecked and can grow into monsters.

We need narratives and we need logic but the tendency today is to throw out logic— supposedly part of a white man’s means of oppression even though logic is found in all advanced cultures— and depend instead on the primacy of narrative, on the supposedly authentic narrative of experiences. But again, this is dangerous; narratives may be mistaken. If my narrative is “love is everything,” I may very well end up beating those who disagree, if I insist on my narrative and at the same time insist that concerns with logic are merely academic and have no place in my world. I’ll simply do what I (mistakenly) believe my narrative tells me, even if it tells me that those who disagree should be beaten over the head for what I judge is “the greater good.”

I believe many people miss what PT says because it’s been heavily promoted and most of us have been trusting of its promoters, as I myself was when I was introduced to it. But very quickly voices highly critical of PT appeared; these voices allow us to reconsider and see this work in a new light.

All references to PT are from the 2022 edition from Chelsea Green Publishing. All references to Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism are from the 2017 Penguin Classics edition.

To begin, PT states that totalitarianism originates from Enlightenment thinking which evolved into mechanistic thinking, and this thinking has become the dominant discourse in Western societies. As said on page 18, “the scientific discourse, like any dominant discourse, has become the privileged instrument of lies, deception, manipulation, and power.” Science, then, has moved from being a project of open discourse and inquiry into an ideology that can’t be questioned, yet it’s open to numerous flaws as we’ve seen in the replication crisis pointed out by such people as Dr. John Ioannidis.

In chapters one and two of PT (“Science and Ideology” and “Science and Its Practical Applications,” respectively) PT lays out the idea that society as a whole is captured by mechanistic thinking. In chapter three, “The Artificial Society,” PT claims that the widespread faith in mechanistic thinking has lead to dehumanization, because, moving away from an intuitive/religious understanding of our place on earth, most of us now believe that “a flawless, humanoid being and a utopian society can be produced from scientific knowledge.” (p. 47) On page 48, PT asserts that totalitarianism is the logical extension of the obsession with science.

In chapter four, “The (Im)measurable Universe,” we’re told that during the Covid crisis, we all acted out a pressing psychological need for certainly and thus believed the numbers put out by health agencies throughout the world. On page 58, PT explicitly says that “we have called the misery that has been so dramatized in the mass media down on ourselves to a large extent….” How? Because we believed the numbers given to us, we believed the data, and the reason we believed the numbers and the data is because we’ve been captured by, and put our blind faith in, the mechanistic world of science.

PT also tells us that society ignored that the cure for Covid might be worse than the disease (p 59) implying that we, the masses, had somehow blinded and hypnotized ourselves to narrow our focus of attention onto Covid-19 and all the threats it might pose.

It’d be appropriate here to pause and ask what PT is talking about and the reality it’s painting for us, and ask about the ontological status of its concepts; that is, what reality do they have? Does what PT claims is real actually exist? What’s the ontological status of PT’s assertions?

Ontology: the branch of metaphysics that deals with the nature of being.

PT repeatedly says that we had widespread faith in mechanistic thinking prior to Covid and that many of us believed that “a flawless, humanoid being and a utopian society can be produced from scientific knowledge.” This is a tranhumanist ideal and this type of thinking was in fact predominant before the First World War. But of course the World War and the one to follow— not to mention the Great Depression— disabused many of the notion that the science of social engineering would lead to perfection rather than to terrible wars and economic collapse. It’d be hard to believe that prior to Covid, any of us had any illusions that technology alone would lead us to a better world: we saw the many problems that greed coupled with technology brought and the human and environmental destruction attendant. Ethics matters: an intuitive grasp of the value of life matters. We knew that.

Further, none of us was captured by the mechanistic mindset prior to, or even during, Covid. This is a fiction: the reality PT wants us to believe existed, simply didn’t exist. We weren’t even atomized prior to Covid, as asserted in chapter three. To be sure there were lonely people in society; society always has lonely people. But what we experienced on the whole was that people enjoyed being together with friends and family, they enjoyed going to ball games, concerts, parks, colleges, restaurants, and bars and for the most part people were civil and decent to each and casual, friendly banter with strangers wasn’t unusual. We even hugged each other. If the doctrines of Christianity were no longer predominant, other spiritual beliefs took their place: despite a smaller church-going population, those with alternative, non-mechanistic spiritual beliefs largely made up for those loses. Even today, few are die-hard materialists.

We all knew as well that life was more than a big mechanistic machine. Anyone who has fallen in love or has had children knows that there’s much more to life than one billiard ball hitting another in endless mechanistic chain reactions.

The picture of a despairing, atomized society waiting to be gobbled up in a mass formation is false. It’s a false ontology: what PT says was real, wasn’t real at all. We can see this for ourselves now, in January, 2023, when Covid is largely over for most people and we simply get on with our lives as before, and we associate with others and we put any atomization caused by Covid regulations themselves— and not by our prior propensity for mechanistic thinking— behind us. Those parts of the country still captured by Covid fear are caught because of government dictates or government-induced fear.

And here, then, is the crux of the problem and where PT goes off the rails. Totalitarianism is not, as PT says, “the belief that the human intellect can be the guiding principle in life and society” (p 175.) That statement is simply absurd on its face— are we supposed to have “non-thinking” guide us, then? No use of our intelligence? Thinking causes totalitarianism?

Totalitarianism is, quite simply, total censorship, total surveillance, and total enforcement. That’s it. It originates in censorship, and in fact the atomization and anxiety during Covid were induced by massive censorship, not by society’s supposed propensity for mechanistic thinking. We believed the data not because we were so confused that we couldn’t distinguish truth from fiction, but because reliable and qualified voices opposed to official data were viciously censored. The mainstream media was blaring fear-messages at us 24/7; it was absolutely relentless, and the health authorities that should have advised us all to “keep calm and carry on” did the exact opposite.

The “masses” were formed by massive censorship. They did not self-hypnotize themselves.

On page 62, PT tells us who constructed the ideologies that guided us, and he names health care workers, families, politicians, academics, experts, pharmaceutical companies, media— in effect, all of us. And these stories became dominant, according to PT, not because of massive censorship on the part of the public health agencies and medical journals and government (including, we now know, the FBI in collusion with social media) of any views opposed to the official, dictated narrative, but because we, the masses, were a priori addicted to seeing only a mechanistic, technocratic utopia. On page 63, PT tells us that we were a society saturated with fear and unease, and therefore selected from a myriad of numbers those that confirmed our fear.

It’s as if all of society were one huge technology-lusting, mechanistically-thinking mass, and nothing was imposed on that mass from outside; it all came from within. We did it to ourselves. There was no “globally coordinated psychological warfare operation” imposed; the fear wasn’t induced and deliberate but magically created because we, the people, were confused and anxious and uncertain and mechanistically blinded prior to Covid and lusted after “data” to confirm our worse fears. Covid, then, only revealed who we really were.

Page 64: “We will see that the flight into false security is a logical consequence of the psychological inability to deal with uncertainty and risk, an ability that has been building up in society for decades, perhaps even centuries.” Is that really true? Is it really true that in our lives we avoid uncertainty and risk, or do we instead know full well, through our collective experience as well as through our individual experience, that life is full of uncertainties and risks? Is PT creating this ontology— this social being that PT claims is real— merely to support a narrative for the mechanism of totalitarianism?

On page 83, PT asserts that we’ve been following the Enlightenment ideology of reason and thus shut out the language of uncertainty depicted in the arts, but we still faced that uncertainty so turned to narcissism and fear, rationality and rules. However, this take on things ignores completely the huge attraction the arts have for us and the proliferation of music and fiction and painting and so on, and the fact that many of us take refuge from our workdays through the arts, whether through turning on the stereo or reading a novel. We have television, too, which certainly doesn’t reinforce a rational, mechanistic world-view. Then there are non-mechanistic pubs, where we often socialize and talk about anything at all but virtually never about how we all dream of a mechanistic utopia.

Concurrent with our technological— not technocratic!— society was a proliferation of thinking about ethics, justice, political systems and governance, individual freedom, the use and abuse of technology and science, and so on. Yet PT views the world as if these things never existed, or if they did, they were all subsumed under a technocratic vision possessed by all of society.

PT asserts that, being psychologically exhausted, bound-in by mechanistic rules, strangers to love, relationships, fulfillment, and the arts, captured by Enlightenment reason and seeking a way out, we look for a master (p 86.) Do we?

On page 91, PT succinctly summarized the mechanism of mass formation (italics):

Society is first gripped by a fanatical, mechanistic ideology. But this is a false ontology: there was no such fanatical society. PT is confusing a technological society, which we are, with a technocratic society, which we are not. We use technology; for the most part, technology doesn’t use us. That said, the danger is that technology now allows for total surveillance and we are indeed in danger of being enslaved by technology and governed by technocrats.

Because of this (non-existent) fanaticism, meaninglessness and social isolation increased.

Hopes were placed on a utopian, technological solution to problems. But already, prior to Covid, we were mature enough to understand that there are simply no pure utopian solutions, except in the minds of fanatical social engineers— technocrats. Most of the population is not fanatical social engineers.

Public space was increasingly dominated by numbers, data, and statistics that blurred fact from fiction. But the truth, exemplified by the replication crisis, is that numbers and data were abused to sell product or theory or political goals or to advance careers, etc. It’s not that we didn’t know truth from fiction; it’s that we didn’t know which numbers to trust in certain areas of research, the medical field being the prime example. But this concern was largely academic and didn’t touch the broader population.

The epidemic of fear and uncertainty made the population yearn for absolute authority. This so-called epidemic is completely fabricated. Prior to Covid, we acted like normal human beings: we went to work, we picked our kids up from school, we shook hands with people and hugged them, we perhaps had dinner with friends, we maybe went to a ballgame or a park on weekends, we went on vacations. The economy was decent and there were no real disruptions to make us full of fear and uncertainty.

The socially fragment population then suddenly reunites into a unit through the process of mass formation. Was it ever as radically fragmented as PT asserts?

In chapter 7, “The Leader of the Masses,” PT asserts that the person doing the hypnotizing during the mass formation is also hypnotized (p 105) and on page 119, PT states that the real masters aren’t the leaders of totalitarian systems but rather the underlying mechanistic ideology. No one knows the full script; everyone is possessed.

It’s appropriate here to ask why does PT assert that we were such atomized masses? Why does PT insist that Enlightenment ideology, in its mechanistic form, leads to totalitarianism? The answer is likely to lie in PT’s frequent references to Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism.

On page 3 of PT, we find a quote from Arendt’s book, page 622:

“The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (i.e., the reality of experience) and the distinction between true and false (i.e., the standards of thought) no longer exist.”

PT means to apply this assessment to the pre-Covid society, in danger of confusing fact and fiction, true and false. But this society was in no way similar to the pre-totalitarian society that Arendt describes, in which near-total terror had played out and the stage was set for the complete and total terror to come. In the sentences just preceding the above quote Arendt says this:

“Just as terror, even in its pre-total, merely tyrannical forms ruins all relations between men, so the self-compulsion of ideological thinking ruins all relationships with reality. The preparation has succeeded when people have lost contact with their fellow men as well as the reality around them; for together with these contacts, men lose the capacity of both experience and thought.”

What’s Arendt talking about? She’s not talking about a mere mechanistic ideology but the grip of a specific ideology, and here, too, PT confuses the intent of the Arendt’s book with PT’s own mechanistic ideology of totalitarianism, for Arendt refers to a specific idea (not a general mode of thought) whose logic leads beyond this world and drives the world to its ultimate illumination. In the case of Nazi Germany, this was the single idea of “a purified race” which would be the apotheosis of human being; for Stalin’s Russia, it was “a classless society” that would finally illuminate the world. In both cases, the specific ideology (i.e., the logic of a specific idea) determined everything, it swept everything up in it, it was arbitrary and capricious and irrational in that it had only its own internal momentum and disregarded this world completely, except in that terrible momentum to achieve the end of a master race or a classless society. The picture Arendt paints of the psychological effects of these specific ideologies is indeed horrible to contemplate as they removed all psychic space between humans and created total, complete terror in which there was no right, no wrong, no fact, no fiction; only total, arbitrary terror as the madness of a single idea, completely un-tethered to reality and driving toward a supposed final illumination, consumed everything.

This is why Arendt could say that the ideal subject for totalitarianism wasn’t the (merely) convinced Nazi or the Communist: it was the people whom terror had already nearly consumed in its merely tyrannical beginning, as a prelude to total terror.

The world that Arendt describes is nothing like the world that was during Covid, even in the most restrictive periods of High Covid. The ideology she describes— the logic of a single idea— isn’t comparable to PT’s broad mechanistic ideology. But a curious thing about PT is that it misses completely a single idea that has been circulating and that could indeed capture the masses in its inexorable logic, a logic that would (supposedly) lead at last to the illumination of the world as it swept through humanity in a potential terror toward its realization, corresponding exactly to what Arendt describes. That idea is simply the innocuous sounding, “stay safe.” And here we have gleamings of a totalitarian biosecurity state that PT says virtually nothing of.

Chapter 8, “Conspiracy and Ideology,” might be considered the heart of PT because the real program of the book is revealed: to demonstrate that there was no conspiracy during Covid 19 to induce fear and instigate a biosecurity state, and there was no attempt to introduce tyranny through the back door of “medical necessity.” Everything during Covid transpired mechanistically. This is ironic for a book premised on condemning mechanistic thinking, but that yet posits a mechanistic flow to mass formation beginning with social anxiety and uncertainty.

It’s important to understand that PT argues that there was no conspiracy during Covid, and thus PT contradicts the statement at the beginning of this essay:

“As we approach 2023, you are now completing and have survived the third year of the largest, most globally coordinated psychological warfare operation in the history of mankind. During this period, on a daily basis, you have experienced the US Government and many western nations deploying highly refined, military-grade fifth generation warfare technologies against their own citizens.”

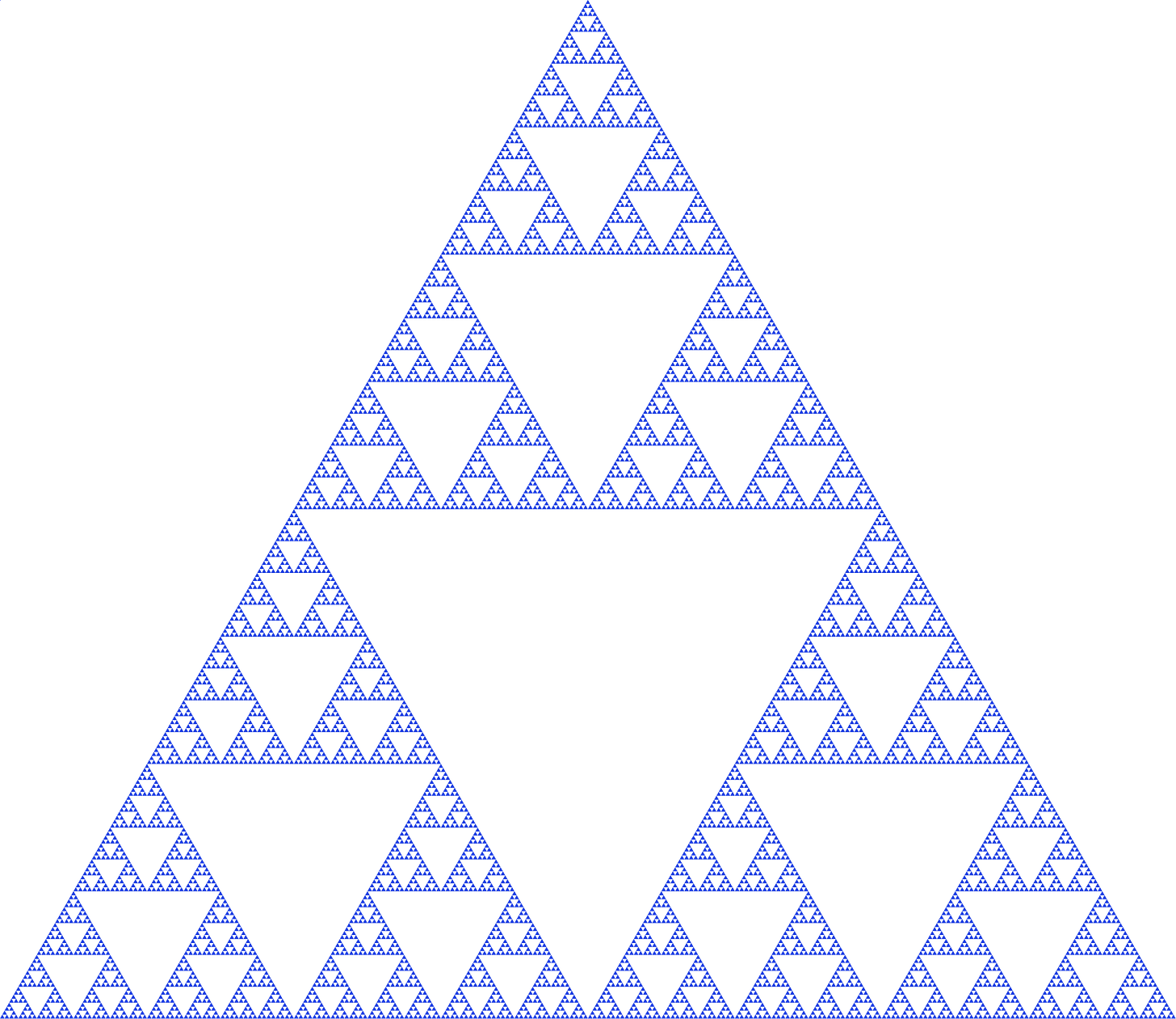

PT uses the Sierpinski triangle as an analogy to what happened during Covid: although the triangle appears to be orchestrated, in truth only a few rules are followed blindly to produce it.

PT’s argument against conspiracy is essentially this: there was no one outside of the mass formation directing it because everyone was in the mass formation. We were all hypnotized. What this means is that we were all a technocratic, or pre-technocratic, society to begin with and any planning was the result of an overall, collective hypnotic social desire to escape the uncertainties of existence.

But let’s look at this line of reasoning. It’s in essence a tautology: it says nothing that isn’t already true. If PT says that all of society is captured in a mechanistic mindset then that means, in essence, that all of civilized humanity was captured. So let’s just shorten this and say, “all of humanity” is within a mechanistic mindset. So there was no one outside doing any conspiring, no orchestration, because there was no one doing this who was outside of humanity: a tautology. This is how PT escapes the conclusion that there was no conspiracy even though he admits that there was a “pseudo-conspiracy” (that is, manipulation and planning.) We’re all human and we’re all mechanistic thinkers, therefore the people planning and orchestrating must be all human and mechanistic thinkers. Even an small conspiracy of orchestrators (in the context of all of humanity, 10,000 people would still be a small number) who really did plan to monitor and manage the entire population would merely be part of the fictitious mechanistic society that PT sets up. This tautological reasoning is a slick trick, to put it bluntly, and one so many have fallen for to excuse PT.

What does PT say about conspiracy theorists? In a nutshell, since there was no conspiracy, then these people are dangerous because, as PT says on page 137, conspiracy thinking itself can give rise to mass formation. On page 138 PT says, “If one wants to slow down the masses, one must do so by psychological means.” Perhaps it would be helpful to sedate conspiratorial thinkers?

Notice that on page 187 PT urges truth-telling— parrhesia— by those not hypnotized by the mass formation. But if there actually is/was/will be a conspiracy, what then? Are we supposed to speak up then? But there is/was/will be no conspiracy! We are all within the mechanistic thinking, and if anyone points out that it’s indeed possible for technocratic thinkers to plan and design to engulf all of humanity in a realm of technological surveillance in order to monitor and manage it for a technocratic “greater good,” then these people are dangerous conspiracy thinker that should be handled psychologically.

The danger of PT’s theory is that it obscures the true nature of totalitarianism, which isn’t mass formation at all: it’s total censorship, total surveillance, and total enforcement, and this can come about without the will of the masses— without their “desire for a master.” It can simply be imposed quietly and almost imperceptibly on those who listen to official news source, and protesting voices will be ignored as if they never existed.

The danger we’re facing is that with the rapid growth of technology, the conveniences of technology can be morphed into a web of total surveillance and total censorship. It’s remarkable that in a book on totalitarianism published in 2022, virtually nothing is said about the insidious dangers that censorship holds for us right here and right now, and that this censorship is indeed the beginning of real totalitarianism: as Hitler said, the first thing must be “an inconceivable wave of propaganda.” We’ve seen an undeniable wave of censorship of medical information at the very least, and political censorship— forbidden by our Constitution— is rampant, yet invisible to those who rely on supposedly “official” yet highly selective news sources. PT is silent on this and instead directs our attention to the need to manage those who imagine conspiracy theories, lest they evolve into dangerous formations that are a threat to our democracy.

I’ll close with a list of fallacies in PT.

Fundamental fallacy of PT: those not hypnotized should speak truth, but not the truth of conspiracy. There was no conspiracy!

False ontology: there is no mechanistic technocratic-like ideology pervading society. A technological society isn’t the same as a technocratic society.

False equivalence: pre-Covid society, and even High Covid society, was nothing like the near-total terror that preceded the great totalitarian societies of the 20st century, as explicated by Hannah Arendt.

False generalization: the few radical technocratic thinkers are projected onto all of society.

Tautological reasoning: the people doing the manipulation are part of “the people” (who are all captured by mechanistic thinking) therefore there is no one outside of the people. This is how PT paradoxically claims that there was manipulation but it never rises to “grand” manipulation.

False premise: conspiracies are always completely secret. Therefore, no conspiracy if not completely secret.

False causation: totalitarianism isn’t due to Enlightenment reasoning but rather to censorship and surveillance.

I’m certain readers could find a number of other fallacies in PT. One can only hope that in the future instead of being lauded everywhere and serving as a psychology for a new world, PT becomes instead a prime example of how the sleep of reason produces monsters.

The Psychology of Totalitarianism is a narrative unchecked by reason and logic, apparently meant to convince those of us watchful against tyranny to not-see what we all see plainly. It is not a “nuanced” analysis, as some have claimed, nor is it subject to interpretation because PT clearly outlines the (supposedly) definitive mechanism for totalitarian, which mechanism obscures the true mechanisms for totalitarianism that lie in total censorship, total surveillance, and total enforcement, regardless of what the masses themselves— we, the people— desire.

Very good and thorough analysis. As I'm sure you know hardly anyone engages in this kind of through intellectual exercise to understand something like totalitarianism or mass formation and mass hysteria. On the surface and as normally used online the mass formation thing works as far as it goes. But obviously a willingness of individuals to honor the processes of both logic and intuition is important. In addition a real effort at communication and free speech.

True we have all been indoctrinated by our so called elites and associates for thousands of years. I do believe it goes well beyond European Enlightenment and have written on that subject. I am more intuitionally based than many seem to be and more based on the using of Occam's razor to comprehend and explain the complexities of complex subjects. You just did that very well . Thank you.

This is brilliant, Jim. I'm going to do an episode on it tomorrow and direct my thoughtful readers who have suggested I read PT to this, where I hope they comment on what they think you're missing. It's not about being right, it's about understanding reality so we can't be manipulated.

I read this slowly and savored it because you're speaking my language. I talk about being ploddingly methodical and logical as my superpower--the Mr. Spock of spirituality, ethics, geopolitics, economics. You had me at "totalitarianism is a political problem, not a psychological problem." I could have stopped there and known that we agreed. But I'm glad I didn't and got so many more proof points and logical arguments!

I'll save the rest of my comments for the episode but there's an older video of mine that speaks to what science is really and why it doesn't lead to mechanistic thinking. It's called Are We Being Manipulated? on Paul Kingsnorth and quotes Dr. Amishi Jha's definition of science as "a pursuit through a process of understanding what is": https://youtu.be/mnAXypCx32o. Oh and I found this one too, while I was looking, that uses Occam's Razor, as KW mentions. It's called Thinking Clearly about Empire on John Campbell: https://youtu.be/Z_4TFXlqZ7Q. Thanks for this great work!